Sunday April 23, 2006 Year B - Easter 2

Acts 4:32-35

Psalm 133

1 John 1:1-2:2

John 20:19-31

Beholding Jesus — in the Flesh

When Jesus was arrested, all the disciples, except Peter, fled. Peter, who followed behind, eventually fulfilled his Lord's prophecy by denying any knowledge or alegience to him three times. He could not bear Jesus' penetrating look and bolted from the courtyard of the high priest. Outside the gates of the compound, he fell on his face, sobbing uncontrolably. Eventually he made his way back to the upper room where the rest of the disciples had gathered.

Throughout the ordeal of the crucifixion, the disciples hid from the authorities for fear that they, too, would be hauled off to be nailed to a Roman Cross. Cloistered away from the world as they were, they had about thirty hours to sit trembling in the damp room, thinking about what had happened, what they had done, what they had lost. They had given up their own lives and livelihood to follow this self-styled prophet. They believed in him, in what he said, in what he did, in who he was. Peter had called him the Messiah, hadn't he? What a Messiah! He ended up getting himself crucified like a common criminal or traitor to the Roman Empire. And what an army they had been. They had fled at the first sign of trouble. If Jesus wanted to start a revolution how could he have put so much trust in men who could not, or would not, stand and fight. Their shame was matched only by their fear.

Throughout the ordeal of the crucifixion, the disciples hid from the authorities for fear that they, too, would be hauled off to be nailed to a Roman Cross. Cloistered away from the world as they were, they had about thirty hours to sit trembling in the damp room, thinking about what had happened, what they had done, what they had lost. They had given up their own lives and livelihood to follow this self-styled prophet. They believed in him, in what he said, in what he did, in who he was. Peter had called him the Messiah, hadn't he? What a Messiah! He ended up getting himself crucified like a common criminal or traitor to the Roman Empire. And what an army they had been. They had fled at the first sign of trouble. If Jesus wanted to start a revolution how could he have put so much trust in men who could not, or would not, stand and fight. Their shame was matched only by their fear.

Then the women came. How hysterical they had been. They actually believed that this man had risen from the grave. They had seen people crucified before. It was Pilate's favorite past time. He particularly liked to line the roads leading to the city with crosses at Passover time.

Jerusalem at Passover time was filled with pilgrims making their pilgrimage to the Holy City to sacrifice at the Temple of the One True God. Pilate wanted them to remember who was incharge. He didn't want them getting any ideas that this god of theirs would actually be able to do anything to thwart the power of mighty Rome.

But the women were insistent. Peter and John had gone to the tomb and had come back verifying that the body was indeed, missing. But that was many hours earlier. That was at dawn and now it was evening.

The disciples had locked themselves in a room because they were afraid. I wonder how long they planned to stay there and whether or when they planed to get on with their lives. The locked room was like a tomb where Jesus' friends were huddling together, paralyzed in their inactivity and hopelessness. I always picture this room as hot and cramped, a place that is no-place, with mortal fear lurking just outside the door.

My own experience of hiding is limited to the time spent in a small bomb shelter in Vietnam. In the middle of the night there came a mortar attack. The siren sounded and woke us all from a light sleep. Eight men clad only in our underwear huddled in this bunker listening to the sounds of mortars exploding nearby and the sound of rifle fire in the near distance. I can only imagine what it must be like to listen breathlessly for footsteps and to wonder if my fragile cover will be ripped away in the next moment. My experience was nothing compared to the plight of the Jews in Nazi Germany and Poland, who hid themselves behind false walls trying to make no sound as the house was methodically searched by the gestapo looking to send them to the camps. But that is exactly the kind of fear that infected the souls of the disciples.

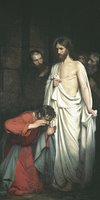

Suddenly Jesus was there. John doesn't tell us how he entered; he is simply there. The disciples must not have recognized him, for he identified himself by showing them his wounded hands and side. This is a common thread through the resurrection stories: Jesus appears in the midst of those closest to him, the people who know and love him, and they don't recognize him. Mary Magdalene mistakes him for the gardener until he calls her by name. The two disciples on the road to Emmaus do not recognize the risen Christ until the end of the journey, when they share a meal with him. Only belatedly do Peter and John realize that the stranger on the shore, directing them to an astonishing catch of fish, is their teacher.

Thomas was not present in the closed-up room at that first meeting. Later, when his friends told him, "We have seen the Lord," he refused to believe unless his eyes could see and his hands could touch and probe Christ's wounded body.

This scepticism earned Thomas the nickname: Doubting Thomas. But he was no more skeptical than the other disciples. They too were not convinced until they were able to place their hand in the nail-scarred hand.

This scepticism earned Thomas the nickname: Doubting Thomas. But he was no more skeptical than the other disciples. They too were not convinced until they were able to place their hand in the nail-scarred hand.

The scriptures are silent about what happened in the ensuing week. But one week later, on Sunday, the first day of the week, they were still hiding in the upper room with the doors locked. And Jesus appeared to them again, just as He had before. He called Thomas to him and invited him to "put your finger here, and see my hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side." This is a powerful invitation. It is an invitation to come close and to experience Jesus’ physical presence, his physical realness. He is saying, "Look closely. Be at home with me. Don't be afraid to touch me--you will neither hurt nor offend me."

The disciples, and especially Thomas, were urged to look at his wounds to make sure that they were in the presence of Christ--not some ghost or imposter, but their friend and teacher. Were the disciples brought up like most of us? Were they taught that it's not polite to stare, particularly not at the hurts, wounds and distortions that afflict others? Were they, like us, schooled to be cautious about touch? Jesus urges them to probe his wounds. This is not a tentative little poke, but the kind of rough, exploratory touching that we experience from babies and small children.

Good mothers tend to be a little bit messy, don't they? At least, their grooming isn't perfect. The touch of a small child, seeking assurance of safety and love, should not be hampered by warnings not to spoil makeup or displace carefully arranged hair. Jesus, our good Lord and our good friend, would pass this test for a loving, embracing presence. He wanted the disciples to go beyond appearances and know him as he was. He was not a “look but don’t touch” kind of Savior.

Most of us present carefully prepared façades. The self that we offer to others is not the product of conscious deception, yet we want no one to disturb the meticulously maintained surface. The message is implicit: Don't look too closely at my wounds, please. By all means feel free to touch me, but don't do the spiritual equivalent of spoling my makeup or mussing my hair--of cracking my surface. You see, my fear is that if you knew what I was really like, you would not love me.

But Jesus is saying, "Be at home with me, and don't be afraid to touch me. You will neither hurt nor offend me." He is setting us an example, but at the same time inviting us into ever greater intimacy with him. He greets our fear and disbelief with loving acceptance, assuring us that he doesn't mind our questions and our probing. This gospel is no ghost story, no holy twilight zone divorced from physical reality or from everydayness. It is an invitation to come close, close enough to see the wounds and feel his risen presence.

Jesus' appearance in the midst of his frightened friends is a story of incarnation, and reminds us that God became one of us and he still comes among us, experiencing and loving our humanity. We are aware of this at Christmas, when we hear that "the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth." Then the churches fill, and even nonbelievers are drawn instinctively by the powerful image of God coming among us in the perfection, loveliness and vulnerability of a little baby boy.

Yet Good Friday is about the incarnation too. Jesus crucified on the cross is a symbol of suffering. It is a powerful statement about human flesh and about its terrible vulnerability. And His Passion reminds us of mankind's almost infinite capacity to both inflict and suffer hurt. Easter comes as a real relief from the uncomfortable physicality of Good Friday.

The resurrection can be a pleasant abstraction: we can ring bells and surround ourselves with lilies and joyous music as we distance ourselves from his broken body. But the risen Christ did not appear to his followers in dreams or visions: he came among them in the homeliness and everydayness of shared walks and meals.

He still comes in everydayness. He still says: see my hands and my feet. Don't avert your eyes from my wounds out of politeness or disgust. Look at them. Put your finger here. Don't be afraid. Remember the incarnation. I came among you first in human flesh--flesh that can be hungry and fed, flesh that can be hurt, even killed. Flesh that can embody God's love.

He comes among us still, mediated through human flesh. See his hands, his side. Touch him, and see.

Psalm 133

1 John 1:1-2:2

John 20:19-31

Beholding Jesus — in the Flesh

When Jesus was arrested, all the disciples, except Peter, fled. Peter, who followed behind, eventually fulfilled his Lord's prophecy by denying any knowledge or alegience to him three times. He could not bear Jesus' penetrating look and bolted from the courtyard of the high priest. Outside the gates of the compound, he fell on his face, sobbing uncontrolably. Eventually he made his way back to the upper room where the rest of the disciples had gathered.

Throughout the ordeal of the crucifixion, the disciples hid from the authorities for fear that they, too, would be hauled off to be nailed to a Roman Cross. Cloistered away from the world as they were, they had about thirty hours to sit trembling in the damp room, thinking about what had happened, what they had done, what they had lost. They had given up their own lives and livelihood to follow this self-styled prophet. They believed in him, in what he said, in what he did, in who he was. Peter had called him the Messiah, hadn't he? What a Messiah! He ended up getting himself crucified like a common criminal or traitor to the Roman Empire. And what an army they had been. They had fled at the first sign of trouble. If Jesus wanted to start a revolution how could he have put so much trust in men who could not, or would not, stand and fight. Their shame was matched only by their fear.

Throughout the ordeal of the crucifixion, the disciples hid from the authorities for fear that they, too, would be hauled off to be nailed to a Roman Cross. Cloistered away from the world as they were, they had about thirty hours to sit trembling in the damp room, thinking about what had happened, what they had done, what they had lost. They had given up their own lives and livelihood to follow this self-styled prophet. They believed in him, in what he said, in what he did, in who he was. Peter had called him the Messiah, hadn't he? What a Messiah! He ended up getting himself crucified like a common criminal or traitor to the Roman Empire. And what an army they had been. They had fled at the first sign of trouble. If Jesus wanted to start a revolution how could he have put so much trust in men who could not, or would not, stand and fight. Their shame was matched only by their fear.Then the women came. How hysterical they had been. They actually believed that this man had risen from the grave. They had seen people crucified before. It was Pilate's favorite past time. He particularly liked to line the roads leading to the city with crosses at Passover time.

Jerusalem at Passover time was filled with pilgrims making their pilgrimage to the Holy City to sacrifice at the Temple of the One True God. Pilate wanted them to remember who was incharge. He didn't want them getting any ideas that this god of theirs would actually be able to do anything to thwart the power of mighty Rome.

But the women were insistent. Peter and John had gone to the tomb and had come back verifying that the body was indeed, missing. But that was many hours earlier. That was at dawn and now it was evening.

The disciples had locked themselves in a room because they were afraid. I wonder how long they planned to stay there and whether or when they planed to get on with their lives. The locked room was like a tomb where Jesus' friends were huddling together, paralyzed in their inactivity and hopelessness. I always picture this room as hot and cramped, a place that is no-place, with mortal fear lurking just outside the door.

My own experience of hiding is limited to the time spent in a small bomb shelter in Vietnam. In the middle of the night there came a mortar attack. The siren sounded and woke us all from a light sleep. Eight men clad only in our underwear huddled in this bunker listening to the sounds of mortars exploding nearby and the sound of rifle fire in the near distance. I can only imagine what it must be like to listen breathlessly for footsteps and to wonder if my fragile cover will be ripped away in the next moment. My experience was nothing compared to the plight of the Jews in Nazi Germany and Poland, who hid themselves behind false walls trying to make no sound as the house was methodically searched by the gestapo looking to send them to the camps. But that is exactly the kind of fear that infected the souls of the disciples.

Suddenly Jesus was there. John doesn't tell us how he entered; he is simply there. The disciples must not have recognized him, for he identified himself by showing them his wounded hands and side. This is a common thread through the resurrection stories: Jesus appears in the midst of those closest to him, the people who know and love him, and they don't recognize him. Mary Magdalene mistakes him for the gardener until he calls her by name. The two disciples on the road to Emmaus do not recognize the risen Christ until the end of the journey, when they share a meal with him. Only belatedly do Peter and John realize that the stranger on the shore, directing them to an astonishing catch of fish, is their teacher.

Thomas was not present in the closed-up room at that first meeting. Later, when his friends told him, "We have seen the Lord," he refused to believe unless his eyes could see and his hands could touch and probe Christ's wounded body.

This scepticism earned Thomas the nickname: Doubting Thomas. But he was no more skeptical than the other disciples. They too were not convinced until they were able to place their hand in the nail-scarred hand.

This scepticism earned Thomas the nickname: Doubting Thomas. But he was no more skeptical than the other disciples. They too were not convinced until they were able to place their hand in the nail-scarred hand.The scriptures are silent about what happened in the ensuing week. But one week later, on Sunday, the first day of the week, they were still hiding in the upper room with the doors locked. And Jesus appeared to them again, just as He had before. He called Thomas to him and invited him to "put your finger here, and see my hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side." This is a powerful invitation. It is an invitation to come close and to experience Jesus’ physical presence, his physical realness. He is saying, "Look closely. Be at home with me. Don't be afraid to touch me--you will neither hurt nor offend me."

The disciples, and especially Thomas, were urged to look at his wounds to make sure that they were in the presence of Christ--not some ghost or imposter, but their friend and teacher. Were the disciples brought up like most of us? Were they taught that it's not polite to stare, particularly not at the hurts, wounds and distortions that afflict others? Were they, like us, schooled to be cautious about touch? Jesus urges them to probe his wounds. This is not a tentative little poke, but the kind of rough, exploratory touching that we experience from babies and small children.

Good mothers tend to be a little bit messy, don't they? At least, their grooming isn't perfect. The touch of a small child, seeking assurance of safety and love, should not be hampered by warnings not to spoil makeup or displace carefully arranged hair. Jesus, our good Lord and our good friend, would pass this test for a loving, embracing presence. He wanted the disciples to go beyond appearances and know him as he was. He was not a “look but don’t touch” kind of Savior.

Most of us present carefully prepared façades. The self that we offer to others is not the product of conscious deception, yet we want no one to disturb the meticulously maintained surface. The message is implicit: Don't look too closely at my wounds, please. By all means feel free to touch me, but don't do the spiritual equivalent of spoling my makeup or mussing my hair--of cracking my surface. You see, my fear is that if you knew what I was really like, you would not love me.

But Jesus is saying, "Be at home with me, and don't be afraid to touch me. You will neither hurt nor offend me." He is setting us an example, but at the same time inviting us into ever greater intimacy with him. He greets our fear and disbelief with loving acceptance, assuring us that he doesn't mind our questions and our probing. This gospel is no ghost story, no holy twilight zone divorced from physical reality or from everydayness. It is an invitation to come close, close enough to see the wounds and feel his risen presence.

Jesus' appearance in the midst of his frightened friends is a story of incarnation, and reminds us that God became one of us and he still comes among us, experiencing and loving our humanity. We are aware of this at Christmas, when we hear that "the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth." Then the churches fill, and even nonbelievers are drawn instinctively by the powerful image of God coming among us in the perfection, loveliness and vulnerability of a little baby boy.

Yet Good Friday is about the incarnation too. Jesus crucified on the cross is a symbol of suffering. It is a powerful statement about human flesh and about its terrible vulnerability. And His Passion reminds us of mankind's almost infinite capacity to both inflict and suffer hurt. Easter comes as a real relief from the uncomfortable physicality of Good Friday.

The resurrection can be a pleasant abstraction: we can ring bells and surround ourselves with lilies and joyous music as we distance ourselves from his broken body. But the risen Christ did not appear to his followers in dreams or visions: he came among them in the homeliness and everydayness of shared walks and meals.

He still comes in everydayness. He still says: see my hands and my feet. Don't avert your eyes from my wounds out of politeness or disgust. Look at them. Put your finger here. Don't be afraid. Remember the incarnation. I came among you first in human flesh--flesh that can be hungry and fed, flesh that can be hurt, even killed. Flesh that can embody God's love.

He comes among us still, mediated through human flesh. See his hands, his side. Touch him, and see.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home